- Home

- Alison Weir

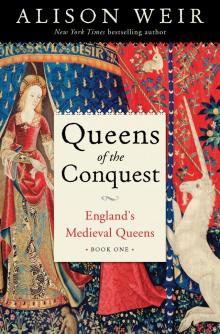

Queens of the Conquest

Queens of the Conquest Read online

Copyright © 2017 by Alison Weir

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

BALLANTINE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, a division of Penguin Random House London, in 2017.

Maps by John Gilkes

Hardback ISBN 9781101966662

Ebook ISBN 9781101966679

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Virginia Norey, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Victoria Allen

Cover illustration: The Lady and the Unicorn (tapestry) (Musée National du Moyen Age et des Thermes de Cluny, Paris)

v4.1_r1

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Maps

England and Wales in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries

Northern Europe in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries

Genealogy

Illustrations

Glossary of British Terms

Introduction

Prologue

“We Are Come for Glory”

Part One: Matilda of Flanders

Chapter 1: “A Very Beautiful and Noble Girl”

Chapter 2: “Great Courage and High Daring”

Chapter 3: “William Bastard”

Chapter 4: “The Greatest Ceremony and Honour”

Chapter 5: “Illustrious Progeny”

Chapter 6: “The Tenderest Regard”

Chapter 7: “The Piety of Their Princes”

Chapter 8: “Without Honour”

Chapter 9: “A Prudent Wife”

Chapter 10: “The Splendour of the King”

Chapter 11: “Power and Virtue”

Chapter 12: “In Queenly Purple”

Chapter 13: “Sword and Fire”

Chapter 14: “Much Trouble”

Chapter 15: “An Untimely Death”

Chapter 16: “The Praise and Agreement of Queen Matilda”

Chapter 17: “Ties of Blood”

Chapter 18: “A Mother’s Tenderness”

Chapter 19: “The Noblest Gem of a Royal Race”

Chapter 20: “Twofold Light of November”

Part Two: Matilda of Scotland

Chapter 1: “Casting Off the Veil of Religion”

Chapter 2: “Her Whom He So Ardently Desired”

Chapter 3: “A Matter of Controversy”

Chapter 4: “Godric and Godgifu”

Chapter 5: “Another Esther in Our Own Time”

Chapter 6: “Lust for Glory”

Chapter 7: “The Common Mother of All England”

Chapter 8: “Most Noble and Royal on Both Sides”

Chapter 9: “Daughter of Archbishop Anselm”

Chapter 10: “Reprove, Beseech, Rebuke”

Chapter 11: “Incessant Greetings”

Chapter 12: “Pious Devotion”

Chapter 13: “A Girl of Noble Character”

Chapter 14: “The Peace of the King and Me”

Chapter 15: “All the Dignity of a Queen”

Chapter 16: “Blessed Throughout the Ages”

Part Three: Adeliza of Louvain

Chapter 1: “Without Warning”

Chapter 2: “A Fortunate Beauty”

Chapter 3: “His Only Heir”

Chapter 4: “Royal English Blood”

Chapter 5: “The Offence of the Daughter”

Chapter 6: “The Peril of Death”

Chapter 7: “Cast Down in Darkness”

Part Four: Matilda of Boulogne, Queen of King Stephen, and the Empress Maud, Lady of the English

Chapter 1: “In Violation of His Oath”

Chapter 2: “Ravening Wolves”

Chapter 3: “A Manly Heart in a Woman’s Body”

Chapter 4: “The First Anniversary of My Lord”

Chapter 5: “Unable to Break Through”

Chapter 6: “Ties of Kinship”

Chapter 7: “Feminine Shrewdness”

Chapter 8: “Touch Not Mine Anointed”

Chapter 9: “His Extraordinary Queen”

Chapter 10: “A Desert Full of Wild Beasts”

Chapter 11: “Treacherous Advice”

Chapter 12: “May Your Imperial Dignity Thrive”

Chapter 13: “Christ and His Saints Slept”

Chapter 14: “Hunger-Starved Wolves”

Chapter 15: “Shaken with Amazement”

Chapter 16: “Dragged by Different Hooks”

Chapter 17: “Sovereign Lady of England”

Chapter 18: “Insufferable Arrogance”

Chapter 19: “Terrified and Troubled”

Chapter 20: “Rejoicing and Exultation”

Chapter 21: “The Lawful Heir”

Chapter 22: “One of God’s Manifest Miracles”

Chapter 23: “Wretchedness and Oppression”

Chapter 24: “A New Light Had Dawned”

Chapter 25: “An Example of Fortitude and Patience”

Chapter 26: “For the Good of My Soul”

Chapter 27: “Carried by the Hands of Angels”

Part Five: The Empress Maud

Chapter 1: “Joy and Honour”

Chapter 2: “The Light of Morning”

Chapter 3: “A Woman of the Stock of Tyrants”

Chapter 4: “A Star Fell”

Appendix I: A Guide to the Principal Chronicle Sources

Appendix II: Letters

Photo Insert

Dedication

Select Bibliography

Notes and References

By Alison Weir

About the Author

Detail Left

Detail Right

Detail Left

Detail Right

Detail Left

Detail Right

Illustrations

Harold Godwinson swears to make William king of England. (Getty Images/UniversalImagesGroup/Contributor)

Thirteenth-century wall paintings of William, Matilda and their eldest son, Robert, from the abbey of Saint-Etienne, Caen. (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Prints and Photography Department)

William sails to England in the Mora, the ship given to him by Matilda. (Getty Images/UniversalImagesGroup/Contributor)

The abbeys founded by Matilda and William in Caen in penance for their forbidden marriage: Matilda’s, Holy Trinity (humberto valladares/Alamy Stock Photo); William’s, Saint-Etienne. (Bridge Community Project/Alamy Stock Photo)

Charter to Holy Trinity bearing the crosses of William and Matilda. (Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Westminster Abbey, where Matilda was crowned queen in 1068. (England: The funeral procession of Edward the Confessor [r. 1042–1066] at the first Westminster Abbey [consecrated 1042] as depicted in scene 26 of the Bayeux Tapestry, 1070–1077/Pictures from History/Bridgeman Images)

Copy of the portrait taken from William’s corpse 435 years after his death. (© Henri Gaud)

William I granting a charter to the City of London. (Illustration from Story of the British Nation, Volume 1, by Walter Hutchinson, London, c.1920. Private Collection/© Look and Learn/Bridgeman Images)

Matilda with her infant son Henry. (Stained glass from Selby Abbey, Yorkshire, 1909 © Malcolm Woodcock)

Matilda as patroness of Gloucester Abbey. (Stained glass from Gloucester Cathedral, 1890s; Angelo Hornak/Alamy Stock Photo)

The footprint of William I’s castle. (Getty Images/Martin Brewster)

Matilda’s tomb in the abbey of Holy Tri

nity, Caen, with its original marble ledger stone. (Wikimedia Commons)

Queen Matilda at work on the Bayeux Tapestry. (Painting by Alfred Guillard, 1848; Collection du MAHB Bayeux © Bayeux—MAHB)

William and Matilda as founders of Selby Abbey, with Abbot Benedict of Auxerre. (Stained glass, Selby Abbey, 1909 © Malcolm Woodcock)

Statue of William the Conqueror in his birthplace, Falaise. (Getty Images/Nicolas Thibaut)

The ill-fated Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy. (Glenn Harper/Alamy Stock Photo)

The Norman Kings from a manuscript of 1250: (top) William I and William II; (bottom) Henry I and Stephen. (“Historia Anglorum,” 1250 [vellum], Paris, Matthew [c.1200–59]/British Library, London, UK/© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Anselm of Aosta, Archbishop of Canterbury. (Hulton Archive/Stringer)

The foundations of Malcolm’s Tower, Dunfermline, where Matilda of Scotland was born. (Wikimedia Commons)

Margaret, Queen of Scots. (Stained-glass window in St. Margaret’s Chapel, Edinburgh Castle. Cindy Hopkins/Alamy Stock Photo)

Matilda as benefactress of St. Alban’s Abbey. (Cotton Nero D. VII, f.7 Matilda, daughter of King Henry I, seated and holding a charter, illustration from Golden Book of St Albans, 1380 [vellum], Strayler, Alan [fl.1380]/British Library, London, UK/© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Statue that may represent Matilda from the west door of Rochester Cathedral. (René & Peter van der Krogt, http://statues.vanderkrogt.net)

Matilda’s brother, David I, King of Scots. (From the Kelso Abbey Charter, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh—reproduced by kind permission of the Duke of Roxburghe)

Matilda’s seal, the earliest one of an English queen to survive. (Empress Maud’s seal/British Library, London, UK/Bridgeman Images)

The wedding feast of the Lady Maud and the Emperor Heinrich V. (Corpus Christi College, Cambridge MS. 373; with thanks to the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge)

Probably Adeliza of Louvain, Henry’s second Queen. (The Shaftesbury Psalter, Lansdowne MS. 383, British Library, British Library, London, UK/© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Henry I mourning the loss of his son in the White Ship disaster. (Royal 20 A. II, f.6v King Henry I on his throne, mourning, illustration from “Chronicle of England” by Peter de Langtoft, c.1307–27 [vellum], English School [fourteenth century]/British Library, London, UK/Bridgeman Images)

Burial of King Henry I at Reading Abbey in January 1136 by Harry Morley, 1916. (© Reading Museum [Reading Borough Council])

The ruthless Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. (Getty Images/ullstein bild/Contributor)

The Norman keep of Arundel Castle, where the Empress Maud sought shelter with Queen Adeliza in 1139. (Motte and Keep at Arundel Castle, eleventh–twelfth century [photo]/Bridgeman Images)

Stone heads, probably of Adeliza and her second husband, William d’Albini, on either side of the east window, Boxgrove Priory, Sussex. (© Alison Gaudion; www.gaudions.co.uk)

Head said to represent Matilda of Boulogne, from Furness Abbey. (Photographer Roy P. Chatfield)

Victorian engraving of Matilda of Boulogne. (Getty Images/Hutton Archive/Stringer)

The great Norman cathedral at Winchester, where Maud was received as “Lady of the English” in 1141. (North transept, built by Bishop Walkelin, 1079–98 [photo]/Winchester Cathedral, Hampshire, UK/Photo © Paul Maeyaert/Bridgeman Images)

Robert, Earl of Gloucester, loyal mainstay of the Empress Maud. (Wikimedia Commons)

King Stephen’s brother, the wily Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester. (The Henry of Blois plaques, England [c.1150] © The Trustees of the British Museum)

The Empress Maud: modern illustration showing the kind of dress she would have worn. (Getty Images/Print Collector/Contributor)

Seal of the Empress Maud. (Seal of Empress Matilda. Engraving, English School, twelfth century [after]/Private Collection/Bridgeman Images)

Artist’s impression of the Empress Maud, based on her seal. (Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo)

Coin showing Stephen and Matilda of Boulogne, struck to mark the King’s restoration in 1141. (Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

St. George’s Tower, Oxford Castle, from which Maud descended by ropes in 1142. (Lesley Pardoe/Alamy Stock Photo)

One of many popular images of Maud, camouflaged in white, making her miraculous escape from Oxford. (Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo)

Wallingford Castle, where Maud sought refuge with the devoted Brian FitzCount. (Graham Mulrooney/Alamy Stock Photo)

The wall encircling the mound and the gatehouse are all that remain of the mighty Devizes Castle, Maud’s headquarters for several years. (© Steve King/flickr)

Hedingham Castle, Essex, where Matilda of Boulogne died. (The Lindsay Family of Hedingham Castle. Photography by Paul Highnam)

Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Contemporary stained glass in Poitiers Cathedral commemorating their marriage in 1152. (Crucifixion; detail of the Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine panel; Stained glass, c.1170; akg-images/Paul M. R. Maeyaert)

Interior of the keep, showing the largest surviving Romanesque arch in Britain. (The Lindsay Family of Hedingham Castle. Photography by Paul Highnam)

The marriage of Maud’s granddaughter, Matilda, to Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony, in 1168. (“Evangeliar Heinrichs des Löwen” [gospel of Henry the Lion]; coronation of Duke Henry and Duchess Mathilda, King Henry of England’s daughter, right. Fol. 171 v. Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Library; akg-images)

Henry II quarreling with Archbishop Thomas Becket. (Becket before Henry II/British Library, London, UK/© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images)

Golden, jewel-studded reliquary cross from the abbey of Valasse. (Musée Departmentale des Antiquités, Rouen, Normandie)

The chapel of Saint-Julien at Petit-Quevilly, founded by Henry II in 1160, and adorned with frescoes that may have been commissioned by Maud. (© Bruno Maury)

Rouen Cathedral, where Maud’s remains were reinterred in 1847. (Zoonar GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo)

Glossary of British Terms

alienate: transfer property or land.

Angevin: native of Anjou.

Anglo-Saxons: the indigenous people of England, or the English. Of Germanic origin.

bourg: an old French word for a town.

canon lawyer: a person trained in the laws, or “canons,” of the Church.

cell: a small room in a monastery or convent, where a religious sleeps.

chronicle: a written account of historical events, often in chronological order.

damsel: a young maid or unmarried girl of gentle birth, the precursor of a maid of honor.

eremitic: a hermit or recluse who lives secluded from the world.

first floor: the floor above the ground floor.

Flemings: the inhabitants of Flanders.

geld: a tax on each hide of land.

girdle: a belt or sash worn around the waist.

hide: Land of approximately 120 acres, which was considered sufficient to support a family.

homage: the swearing of fealty, or loyalty, to an overlord.

honor: a great feudal lordship comprising dozens or hundreds of manors, held by great magnates (tenants-in-chief) of the Crown.

incorrupt: well preserved, as of a corpse.

knight service: the provision of knights for military service owed to a feudal overlord in return for tenure of land.

palfrey: a lightweight, docile horse favored by women. It could amble at a slow place across long distances.

relic: the human remains or surviving possessions of a saint.

religious: a monk or nun.

screens passage: a narrow corridor within the body of a medieval hall, separating the rest of the hall from the service end. Entry into the hall from the passage was through archways or doors in a wooden screen, which mi

ght be carved and decorated, and sometimes supported a minstrels’ gallery above.

slighting: the deliberate destruction of a castle to the point where its defenses are rendered useless.

styled: a formal way of designating or entitling a person.

subjects: the people of a kingdom (or feudal state) who lived under the authority of their king/duke/count or their reigning queen/duchess/countess. The wives of sovereign kings/dukes/counts did not have subjects.

temporal: worldly, as opposed to spiritual.

tithe: a tax of a tenth on rents or produce, raised for the support of the clergy or religious houses.

translate: remove a saint’s body or relics to another place.

wheel of Fortune: a popular medieval symbol of constant change, ephemeral happiness and the fleetingness of prosperity, which appears in manuscripts and stained glass.

Introduction

The saga of England’s medieval queens is vivid and stirring, packed with tragedy, high drama and even comedy. It is a chronicle of love, passion, intrigue, murder, war, treason, betrayal and sorrow, peopled by a cast of heroines, villains, Amazons, stateswomen, adulteresses and lovers. Much, of course, is obscured by time and a paucity of detail—and yet enough survives to reconstruct a dramatic tale. My aim in this book is to piece together the fragments, strip away centuries of romantic mythology and legends that obscure the truth about these queens, and delve beyond the medieval prejudice, credulity and superstition in contemporary sources to achieve a more balanced and authentic view.

Richard III and the Princes in the Tower

Richard III and the Princes in the Tower Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy

Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn

The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn Six Wives of Henry VIII

Six Wives of Henry VIII Elizabeth of York: A Tudor Queen and Her World

Elizabeth of York: A Tudor Queen and Her World Captive Queen

Captive Queen Innocent Traitor

Innocent Traitor The Marriage Game

The Marriage Game A Dangerous Inheritance

A Dangerous Inheritance Katherine of Aragón: The True Queen

Katherine of Aragón: The True Queen The Marriage Game: A Novel of Queen Elizabeth I

The Marriage Game: A Novel of Queen Elizabeth I Princes in the Tower

Princes in the Tower Anne Boleyn: A King's Obsession

Anne Boleyn: A King's Obsession Traitors of the Tower

Traitors of the Tower Mistress of the Monarchy: The Life of Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster

Mistress of the Monarchy: The Life of Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster Queens of the Conquest: England’s Medieval Queens

Queens of the Conquest: England’s Medieval Queens Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Life

Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Life Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley Henry VIII: The King and His Court

Henry VIII: The King and His Court Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England

Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England Katheryn Howard, the Scandalous Queen

Katheryn Howard, the Scandalous Queen Arthur- Prince of the Roses

Arthur- Prince of the Roses The Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses Eleanor of Aquitaine: By the Wrath of God, Queen of England

Eleanor of Aquitaine: By the Wrath of God, Queen of England Mary Boleyn: The Great and Infamous Whore

Mary Boleyn: The Great and Infamous Whore Jane Seymour: The Haunted Queen

Jane Seymour: The Haunted Queen Anna of Kleve, the Princess in the Portrait

Anna of Kleve, the Princess in the Portrait Lancaster and York: The Wars of the Roses

Lancaster and York: The Wars of the Roses The Grandmother's Tale

The Grandmother's Tale The Princess of Scotland (Six Tudor Queens #5.5)

The Princess of Scotland (Six Tudor Queens #5.5) The Lady Elizabeth

The Lady Elizabeth Katherine Swynford: The Story of John of Gaunt and His Scandalous Duchess

Katherine Swynford: The Story of John of Gaunt and His Scandalous Duchess The Curse of the Hungerfords

The Curse of the Hungerfords The Lost Tudor Princess: The Life of Lady Margaret Douglas

The Lost Tudor Princess: The Life of Lady Margaret Douglas Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine Mistress of the Monarchy

Mistress of the Monarchy The Lost Tudor Princess

The Lost Tudor Princess Henry VIII

Henry VIII Anne Boleyn, a King's Obsession

Anne Boleyn, a King's Obsession A Dangerous Inheritance: A Novel of Tudor Rivals and the Secret of the Tower

A Dangerous Inheritance: A Novel of Tudor Rivals and the Secret of the Tower Elizabeth of York

Elizabeth of York Katherine of Aragon, the True Queen

Katherine of Aragon, the True Queen Katherine Swynford

Katherine Swynford Wars of the Roses

Wars of the Roses Queens of the Conquest

Queens of the Conquest Mary Boleyn

Mary Boleyn Britain's Royal Families

Britain's Royal Families The Tower Is Full of Ghosts Today

The Tower Is Full of Ghosts Today Life of Elizabeth I

Life of Elizabeth I Anne Boleyn A King's Obssession

Anne Boleyn A King's Obssession Lancaster and York

Lancaster and York Jane Seymour, the Haunted Queen

Jane Seymour, the Haunted Queen Queen Isabella

Queen Isabella The princes in the tower

The princes in the tower